The Zulu are reputedly one of the most disciplined groups of Negroes in Africa, perhaps several cuts above the Blacks that had been enslaved and sold by other Blacks and were brought to North America. Yet four thousand Zulus were held off by about 150 British soldiers and auxiliaries, with only about 11% fatality on the British side. How much easier, then, to deter a disorganized and opportunistic mob of such Blacks as exist in the USA.

When we White men comport ourselves as White men, and use our gifts of self-control, planning, and ingenuity, even greatly superior numbers of Blacks have no chance against us. The main element in the Blacks’ favor, as the film Zulu does portray accurately, is a lot of noise and intimidation.

It could be said that the Blacks generally contributed to their own defeat in the Zulu War by failing to make good use of the advantages that they had. They never made haste to exploit opportune moments for attack (which gave the White men a chance to fortify their positions) and they never learned from their mistakes. In attack, they continued to concentrate their warriors in a double-column formation called the bull’s horns (not portrayed in Zulu), which perhaps had a symbolic meaning for them, even though it maximized the European soldiers’ ability to mow them down with a hail of bullets. Failure to take account of circumstances and think ahead seems to be the weakness of Negroes everywhere.

Rorke’s Drift

On the 20th of January, however, a large portion of the second column, under Colonel Durnford, Royal Engineers, arrived at Rorke’s Drift and encamped. Their stay was brief, for they were summoned to the fatal camp of Insandhlwana on the morning of the 22d, Colonel Durnford leaving a company of the Natal Native Contingent, under Captain Stephenson, to strengthen the little post. It became evident from various circumstances that Colonel Glyn’s column was encountering a stronger resistance than had been anticipated, and that, as the enemy were in force within a few miles, they might make a rapid descent upon the weakly guarded line of communications.

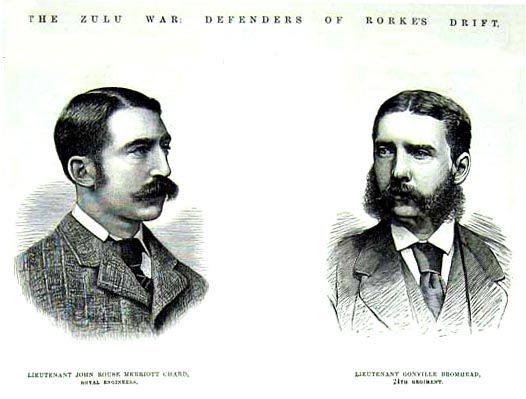

It was known that two companies of the first battalion of the Twenty-fourth were at Helpmakaar, ten miles distant, and Major Spalding resolved to go there at once in order to bring them up as a reinforcement to Lieutenant Bromhead’s force. In his absence, Lieutenant Chard became senior officer at Rorke’s Drift, and responsible for its well-being.

Although on the 22d of January there was thus a feeling of uneasiness at the river post, nothing had occurred till some hours after midday to cause any special alarm to its garrison. We may believe that a general plan of action had been considered if an attack should be made upon it, but in the meantime all the officers and men were engaged in their usual employments. Lieutenant Chard was at the ponts, and Lieutenant Bromhead was in his little camp hard by the store and hospital. Shortly after three P.m. two mounted men were seen galloping at headlong speed towards the ferry from Zululand. There is little difficulty in recognizing messengers of disaster, the men who ride with the avenger of blood close on their horses’ track, and Chard, who met them, knew that something terrible had happened. His worst anticipations were more than realized when the two fugitives — Lieutenant Adendorff, of the Native Contingent, and a Natal volunteer — told their story: the camp at Insandhlwana had been attacked and taken by the enemy, of whom a large force was now advancing on Rorke’s Drift.

Now occurred the first incident which testified to the spirit which animated the small force on the banks of the Buffalo. The ferryman — Daniells —and Sergeant Milne, of the Third Buffs (who was doing duty with the Twenty-fourth), proposed that they should be allowed to moor the two ponts in the middle of the river, and offered, with the ferry-guard of six men, to defend them against attack — a brave thought, indeed, but it was put aside. Chard was too good a soldier to divide his few men in any way. He saw at once that the commissariat stores and hospital would require every available rifle for their defence, and that the safety of every other place was comparatively a very minor consideration.

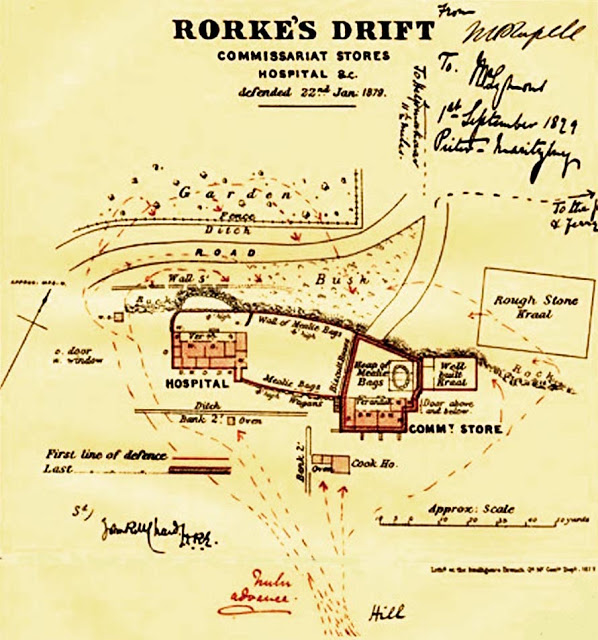

The three officers held a hurried consultation, and prompt use was made of all ordinary expedients of war, while materials never before employed in fortification were pressed into service. The store and hospital were loop-holed and barricaded, the windows and doors blocked with mattresses; but it was necessary to connect the defence of the two buildings by a parapet. There were no stones at hand with which to build a wall, and if there had been, there was no time to make use of them; the hard, rocky soil could not be dug and formed into ditch and breastwork; but there was a great store of bags of mealies, or the grain of Indian corn, which had been collected as horse provender for the army. Assistant-Commissary Dunne suggested that these should be used in the fashion of sand-bags for the construction of the required parapet.

Everybody labored with the energy of men who know that their safety depends on their exertions. Chard and Bromhead, Surgeon Reynolds and Dunne not merely directed, but engaged most energetically in the work of preparation.

When the alarm was first given it was intended to remove the worst cases from the hospital to a place of safety, and two wagons were prepared for the purpose; but it was found that the attempt to move the patients at the slow pace of ox-teams when the Zulus were so close at hand would only result in offering them as easy victims to the murderous assegai. The two wagons were therefore used as part of the defences, and mealie bags were piled underneath and upon them, so that each formed a strong post of vantage.

But if the gallant English officers who had striven so hard and with so much military genius to make their position tenable looked forward to this amount of support, they were destined to grievous disappointment and mortification. At 4.15 P.m. the sound of firing was heard behind a hill towards the south, and told that the vedettes of the Native Horse were engaged with the enemy. Their officer returned, reporting that the Zulus were close at hand, and that his men would not obey orders. Chard and his comrades had the sore trial of seeing them all moving off towards Helpmakaar, leaving the garrison to its fate.

Nor was this all. The evil example was only too soon followed. Captain Stephenson’s company of the Native Contingent also felt their hearts fail, and, accompanied by their commander, also fled from the post of duty.

But this first attack was only the effort of the enemy’s advanced guard. Masses of warriors followed and flowed over the elevated southward ledge of rocks overlooking the buildings. Every cave and crevice was quickly filled, and from these sheltered and commanding positions they opened a heavy and continuous fire. It was fortunate that the spoil in rifles and ammunition taken at Insandhlwana was not yet available for use against the English, as at Kambula and later engagements, but the enemy’s firearms were still the old muskets and rifles of which they had long been in possession. Even so, at the short range these were sufficiently effective, and, in the hands of better marksmen than Zulus usually are, might have inflicted crushing losses.

The misfortune of the extreme hurry in the preparations for defence was now painfully apparent. In strengthening any position for defensive occupation one of the first measures taken by a commander is to clear as large an open space as possible round the parapet or fortifications which he proposes to hold. All ditches and hollows should be filled up; all buildings, walls, and heaps of refuse should be pulled down and scattered; all trees, shrubs, and thick herbage should be cut and removed; so that no attack can be made under cover, no safe place may be found from which deliberate fire may be delivered, or any movement can be made by an enemy unseen, and therefore unanticipated.

At Rorke’s Drift, not only were the buildings and parapets overlooked and commanded to the southward by a rocky hill full of caves and lurking-places, but there was a garden to the north, a thick patch of bush which was close to the parapet, a square Kaffir house and large brick oven and cooking trenches, besides numerous banks, walls, and ditches, all of which offered a shelter to the enemy, which they were not slow to profit by. The post was encircled by a dense ring of the foe, and from every side came the whistle of their bullets.

Up till this time, though several men had been wounded, no one had been struck dead. Suddenly a whisper passed round among the Twentyfourth, “Poor old King Cole is killed.” Private Cole, who was known by this affectionate barrack-room nickname, was at the parapet when a bullet passed through his head, and he fell doing his duty — a noble end.

If the Zulu fire was telling, however, the steady marksmanship of the English officers and men was still more effective. Private Dunbar, of the Twenty-fourth, laid low a mounted chief who was conspicuous in directing the enemy, and immediately afterwards shot eight warriors in as many successive shots. Everywhere the officers were present with words of encouragement, exposing themselves fearlessly and showing that iron coolness and self-possession which rouses such confidence and emulation in soldiery on a day of battle.

Assistant-Commissary Dunne — a man of great stature and physique, with a long, flowing beard — was continually going along the parapet, cheering the men and using the rifle with deadly effect. There was a rush of Zulus against the spot where he was, led by a huge man, whose leopard-skin kaross marked the chief. Dunne called out “Pot that fellow!” and himself aimed over the parapet at another, when his rifle dropped from his hand, and he spun round with suddenly pallid face, shot through the right shoulder. Surgeon Reynolds was by his side at once, and bound up the wound.

The muzzles of the opposing firearms were almost touching each other, and the discharge of a musket blew the broad “dopper” hat from the head of Corporal Schiess, of the Natal Native Contingent. This man (a Swiss by birth), who had been a patient in hospital, leaped on to the parapet and bayoneted the man who fired, regained his place, and shot another; then, repeating his former exploit, again leaped on the top of the mealie bags and bayoneted a third. Early in the fight he had been struck by a bullet in the instep, but, though suffering acute pain, he left not his post, and was only maddened to perform deeds of heroic daring.

It has been said that the building had a thatched roof, and the Zulus not only strove to force an ingress, but used every expedient to set the thatch on fire, and thus to destroy the poor stronghold which so long mocked at their attempts to take it. While many of the patients whose ailments were comparatively slight had risen from their pallets and taken an active part in the defence, there were several poor fellows, utterly helpless, distributed among the different wards; and it is difficult to conceive a situation more trying than theirs must have been, listening to the demoniac yells of the savages, only separated from them by a thin wall, thirsting for their blood. At every window were one or two comrades, firing till the rifles were heated to scorching by the unceasing discharge. Bullets splashed upon the walls, and the air reeked with dense, sulphurous smoke. The combatants may have been excited and carried away by the mad fury of battle; but to men depressed by disease, weakened and racked with pain, truly the minutes must have been long and terrible in their mental and physical suffering.

Shortly after five o’clock the Zulus had been able so far to break down the entrance to the room at the extreme end of the hospital that they were able to charge at the opening; but Bromhead was there, and drove them back time after time with the bayonet. As long as the enclosure was held, they failed in every fierce attempt.

Private Joseph Williams was firing from a small window hard by, and on the next morning fourteen warriors were found dead beneath it, besides others along his line of fire. When his ammunition was expended, he joined his brother, Private John Williams, and two of the patients who also had fired their last cartridge, and with them guarded the door with their bayonets. No longer able to keep their opponents at a distance, the four stood grimly resolute, waiting till the door was battered in and they stood face to face with the foe.

But now it was known that the hospital must be abandoned, and as the usual path was occupied by the enemy, a way had to be made through the partition walls. John Williams and the two patients succeeded in making a passage with an axe into the adjoining room, where they were joined by Private Henry Hook. John Williams and Hook then took it in turn to guard the hole through which the little party had come, with the bayonet, and keep the foe at bay, while the others worked at cutting a further passage. In this retreat from room to room, another brave soldier, Private Jenkins, met the same fate as did Joseph Williams, and was dragged to his death by the pursuers. The others at last arrived at a window looking into the enclosure towards the storehouse, and, leaping from it, ran the gauntlet of the enemy’s fire till they reached their comrades behind the biscuit-box retrenchment. To the devoted bravery and cool resource of Private John Williams and Hook, eight patients, who had been in the several wards which they had traversed, owed their lives. If it had not been for the assistance of these two gallant men, all the eight would have perished where they lay. These, however, were only some of the hairbreadth escapes from the hospital, and only some of the deeds of stubborn hardihood performed in it.

A few of the sick men were half carried, half led, by chivalrous comrades across the enclosure to the retrenchment, but many had to make their own way over the space now swept by the Zulu bullets, and that that space was clear was due to the steady fire maintained by Chard, which prevented the Zulus themselves from leaving the spots where they were under cover. Trooper Hunter, Natal Mounted Police, a very tall young man, who had been a patient, essayed the rush to safety, but he was hit and fell before he reached his goal. Corporal Mayer, Natal Native Contingent, who had been wounded in the knee by an assegai-thrust in one of the early engagements of the campaign, Bombardier Lewis, Royal Artillery, whose leg and thigh were swollen and disabled from a wagon accident, and Trooper Green, Natal Police, also a nearly helpless invalid, all got out of a little window looking into the enclosure. The window was at some distance from the ground, and each man fell in escaping from it. All had to crawl (for none of them could walk) through the enemy’s fire, and all passed scatheless into the retrenchment except Green, who was struck on the thigh. In one of the wards facing the hill on the south side of the hospital, Privates William Jones and Robert Jones had been posted. There were seven patients in the ward, and these two men defended their post till six of the seven patients had been removed. The seventh was Sergeant Maxfield, who, delirious with fever, resisted all attempts to move him. Robert Jones, with rare courage and devotion, went back a second time to try to carry him out, but found the ward already full of Zulus, and the poor sergeant stabbed to death on his bed.

It has been mentioned that a wounded prisoner was being treated in the hospital. So much had he been impressed by the kindness which he had received, that he was anxious to assist in the defence. He said “he was not afraid of the Zulus, but he wanted a gun.” His new-born goodwill was not, however, tested. When the ward in which he lay was forced, Private Hook, who was assisting the Englishmen in the next room, heard the Zulus talking to him. The next day his charred remains were found in the ashes of the building.

That communication was kept up with the hospital at all, and that it was possible to effect the removal of so many patients, was due in great part to the conduct of Corporal Allen and Private Hitch. These two soldiers together, in defiance of danger, held a most exposed position, raked in reverse by the fire from the hill, till both were severely wounded. Their determined bravery had its result in the safety of their comrades. Even after they were incapacitated from further fighting, they never ceased, when their wounds had been dressed, to serve out ammunition from the reserve throughout the rest of the combat.

We have seen that, from the want of interior communication, it had been necessary for those who did escape to cut their way from room to room. Alas! to some of the patients, it had been impossible for the anxious leader and his stanch, willing followers to penetrate. Defeated by the flames and by the numbers of their opponents, Chard records in his official despatch, “With the most heartfelt sorrow, I regret we could not save these poor fellows from their terrible fate.”

While in the hospital the last struggle was going on, Chard’s unfailing resource had provided another element of strength to his now restricted line of defence, and had formed a place of comparative security for the reception of his wounded men. In the small yard by the storehouse were two large piles of mealie bags. These, with the assistance of two or three men and Dunne, who, severely wounded as he was, continued working with unabated energy and determination, he formed into an oblong and sufficiently high redoubt. In the hollow space in its center were laid the sick and wounded, while its crest gave a second line of fire, which swept much of the ground that could not be seen by the occupiers of the lower parapets. As the intrepid men were making this redoubt, their object was quickly detected by the enemy, who poured upon them a rain of bullets; but fortunately unhurt, they completed their work.

The Zulu losses had been tremendously heavy; but still they pressed their unremitting attack. Rush after rush was made right up to the parapets so strenuously held, and their musketry fire never slackened.- The outer wall of the stone kraal on the east of the store had to be abandoned, and finally the garrison was confined to the commissariat store, the enclosure just in front of it, the inner wall of the kraal, and the redoubt of mealie bags.

But the steadfastness of the defenders was never impaired. Still every man fired with the greatest coolness. Not a shot was wasted, and Rorke’s Drift Station remained still proudly impregnable. At 10 P.m. the hospital fire had burnt itself out, and darkness settled over defence and attack. It was not till midnight, however, that the Zulus began to lose heart, and give to the garrison some breathing space and repose. Desultory firing still continued from the hill to the southward, and from the bush and garden in front; but there were no more attacks in force, and the stress of siege was practically over.

The dark hours were full of anxiety, and even the stout hearts which had not quailed during the long period of trial that was past must have had some feeling of disquietude for the morrow, lest wearied, reduced in numbers, and with slender supply of water, they should be called upon to meet renewed efforts made by a reenforced foe.

The dawn came at last, and the eyes of all were gladdened by seeing the rear of the Zulu masses retiring round the shoulder of the hill from which their first attack had been made. The supreme tension of mind and body was over, and if the struggle had been long and stern the victory was for the time complete. How bitterly it had been fought out was shown by the piles of the enemy’s dead lying around, and by the silence of familiar voices when the roll was called. There was yet no rest. The enemy might take heart and return, for, though many of their warriors had seen their last fight, their numbers were so overwhelming, and they must have known so well how close had been the pressure of their attack, that they might well think that, with renewed efforts, success was more than possible.

Patrols were sent out to collect the arms left lying on the field. The defences were strengthened, and, mindful of the fate of the hospital, a working party was ordered to remove the thatch from the roof of the store. The men who were not employed otherwise were kept manning the parapets, and all were ready at once to snatch up their rifles and again to hold the post which they had guarded so long. A friendly Kaffir was sent to Helpmakaar, saying that they were still safe, and asking for assistance.

About seven A.m. a mass of the enemy was seen on the hills to the southwest, and it seemed as if another onslaught was threatened. They were advancing slowly when the remains of the third column appeared in the distance, coming from Insandhlwana, and, as the English approached, the threatening mass retired, and finally disappeared.

In telling the story of the events of the 22d, it has been said that Major Spalding left Rorke’s Drift to seek reinforcements at Helpmakaar. There he found two companies of the Twentyfourth, under Major Upcher, and with them he at once commenced to march to the river post. On their way they met several fugitives who asserted that the place had fallen, and when they arrived within three miles of their destination, a large body of Zulus was found barring the way, while the flames of the burning hospital could be seen rising from the river valley. It was only too probable that if they went on they would merely sacrifice to no purpose the only regular troops remaining between the frontier and Pietermaritzburg. Helpmakaar was the principal store depot for the center column, full of ammunition and supplies, and it seemed best that its safety should, at any rate, be provided for as far as possible. The two companies were therefore ordered to return, and preparations for the defence of the stores were commenced.