“And something I wanted to point out to you. You know, there are many pictures about the Russians liberating Auschwitz, and there is never any snow. And the snow was honestly that high (indicating several feet of snow). And, so I have some connection with the Russian Embassy, and I was there once, and I said: something puzzles me, those photos are fakes, because there is no snow. And they said: well, yes, they are not fakes, but when the army came they didn’t have cameras, they didn’t photograph; so, only much later, when they realized we should have pictures of it, they took pictures like you see now. But this is definitely not in Auschwitz, and not the liberation of Auschwitz.

“There were not that many … children – and [the pictures show] no snow!” (Eva Schloss, Good Morning Britain, 27 January 2020)

This attack on the claim to authenticity of images used in propaganda about Auschwitz and the Holocaust is of the highest importance, because whenever it is suggested that the gas-chamber story might not be true, the first reaction is almost always: What about the pictures? Are you saying that those are fake?

It turns out that, yes indeed, some of them definitely are fake — and we can cite an Auschwitz survivor as our authority for that fact.

The fact that there was snow in late January when the Red Army arrived at Auschwitz is not controversial. It is admitted, for example, in Irmgard von zur Mühlen’s 1985 documentary The Liberation of Auschwitz. The memoir Eva’s Story mentions that the ground was covered with snow several times during February, and never indicates a time when this was not the case, until Soviet authorities finally decided to evacuate civilians from the Auschwitz complex.

Significantly, snow is lacking from nearly all of the visually shocking scenes that are supposed to represent Auschwitz at the time of the “liberation.”

In 1985 Soviet cameraman Alexander Vorontsov admitted that all barracks-scenes from Auschwitz were staged, making excuses for the deception:

“Initially, we did not film the misery inside the barracks. After evacuating the camp on January 19, the SS cut off the electricity. Because initially our camera crews had no lights, we could not shoot indoors. The prisoners had to be transported as quickly as possible, because they were starving to death, and almost frozen.” (The Liberation of Auschwitz, 11:04-11:26)

The narrator tells us that the barracks-scenes were dramatized with Polish women “after the snow had melted.” We are supposed to trust that the dramatization was faithful to reality. Is Soviet propaganda trustworthy?

|

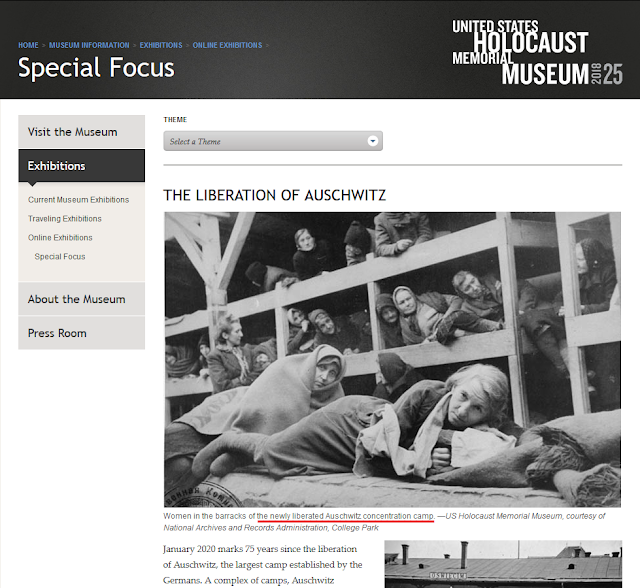

| The USHMM in 2020 still presents this scene — a fraud exposed as long ago as 1985 — as if it were genuine. |

Further undermining the credibility of Soviet documentary film, Vorontsov says that the original idea of how to dramatize the liberation of Auschwitz was completely different from the form that Soviet Auschwitz-propaganda eventually took.

In the original cinematic vision of the liberation of Auschwitz it did not seem to occur to the Soviet cinematographers to show emaciated corpses. (Perhaps they hadn’t seen any?) Instead they showed healthy-looking prisoners anxiously waiting at the gate and cheering when the Red Army arrived to set them free.

In those scenes, there is no snow on the ground, nor on the roofs of the buildings, which indicates that this film was not made immediately after the arrival of the Red Army.

Furthermore, this filming must have been done after the general evacuation in which Eva Schloss participated, since she told Good Morning Britain that the Red Army had no cameras, and her memoir gives no account of any movie being made. Based on the vague chronology in Eva’s Story this evacuation seems likely to have happened in March (rather than February as she said in one interview; if in February it would have had to be very late February). The filming of the first conceptualization of the liberation of Auschwitz, then, must have happened later than that.

Here is an important fact. Although the Red Army had arrived at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration-camp complex on 27 January 1945, Soviet propaganda did not immediately give Auschwitz the importance that it has today. The narrator of The Liberation of Auschwitz tells us:

“The Soviet press agency TASS did not inform the world about the scale of crimes committed in Auschwitz until May 7, 1945. (The Liberation of Auschwitz, 49:41)

Why did it take so long?

The beginning of this kind of Auschwitz-propaganda may have arisen from emulation of British and American camp-liberation propaganda. More than two months after the Red Army arrived at Auschwitz, the Western Allies captured Buchenwald (11 April), Bergen-Belsen (15 April), Dachau (27 April), etc. The timing suggests that this new Soviet Auschwitz-propaganda was inspired by Anglo-American camp-liberation propaganda.

The 1945 Soviet propaganda-film Auschwitz (Oświęcim ) (made from about 20 minutes of selected footage, with German-language narration) is called a “film-document” and is supposed to prove “horrific crimes.” What happens to that pretense when it is admitted that parts of the movie are dramatizations? In particular, the movie shows the now admittedly staged scene of the women in the Auschwitz barracks. The narrator evokes pity by emphasizing that they were all seemingly harmless elderly women:

“Warum ermorderten die Nazihenker diese armen alten Frauen?” (Auschwitz (Oświęcim ), 04:08)

“Why did the Nazi hangmen murder these poor old women?”

This 1945 production of course gives no indication that the scene was staged.

The narration in Auschwitz (Oświęcim ) clarifies that one famous scene is definitely fraudulent. A pitiable group in striped uniforms crowds at the fence, as we are told:

“Und so fand sie die Rote Armee. Die Sowjetkämpfer haben die Deutschen aus Auschwitz vertrieben. Den überlebenen Gefangenen haben sie erklärt: Ihr seid frei! Frei für immer! Die Unglücklichen aber konnten es zuerst gar nicht fassen.”

“And this is how the Red Army found them. The Soviet fighters drove the Germans out of Auschwitz. They declared to the surviving prisoners: You are free! Free forever! At first, the unfortunates could not believe it.”

With this original narration from 1945, indicating that the scene is supposed to represent the very moment of the arrival of the Red Army at Auschwitz, the fraud becomes obvious — because, as Eva Schloss points out, there is no snow.

The memoir Eva’s Story contradicts the whole narrative (whether the 1945 or 1985 version) that images of “the liberation of Auschwitz” are supposed to support. We are supposed to believe that the Red Army made horrible discoveries when they arrived at Auschwitz, and immediately took great interest in the liberated prisoners and their wellbeing. In fact, the behavior of the Red Army during February and late January 1945 as described in Eva’s Story does not reflect any great sense of importance about Auschwitz-Birkenau or its inhabitants. The Birkenau women’s camp, according to Eva Schloss, was not even permanently occupied by the Red Army, nor was any special effort made to help its inhabitants for at least several weeks after the so-called liberation. Official Soviet solicitude for the wellbeing of the inhabitants of the Auschwitz complex was invented retroactively, and supported with dramatizations.

This is a greatly condensed version of an article that can be read in full from CODOH.