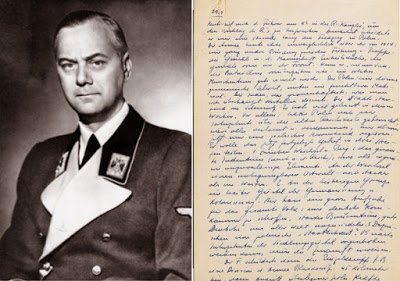

Alfred Rosenberg’s diary, spanning Spring 1936 to Winter 1944, disappeared after the war (stolen by Jewish prosecutor Robert Kempner) but was rediscovered in 2013.

The diary, touted by Henry Mayer of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum as “the most revealing Nazi documents ever found,” turns out (as reported by CODOH’s David Merlin) not to support the Jewish Holocaust story at all. Robert K. Wittman, a former FBI-agent who co-authored a book about the diary, admits it:

“There is no place in the diary where we have Rosenberg or Hitler saying that the Jews should be exterminated…. All it said was ‘move them out of Europe.’ ” [S.F. Kovaleski, NYTimes, 30 March 2016]

This is consistent with Rosenberg‘s testimony at Nuremberg. Having heard the accusation of a conspiracy to annihilate Slavs and Jews, Rosenberg declared that he had no part in it:

Besides repeating the old accusations, the prosecutors have raised new ones of the strongest kind; thus they claim that we all attended secret conferences in order to plan a war of aggression. Besides that, we are supposed to have ordered the alleged murder of 12,000,000 people. All these accusations have been collectively described as “genocide” — the murder of peoples. In this connection I have the following to declare in summary.

I know my conscience to be completely free from any such guilt, from any complicity in the murder of peoples. Instead of working for the dissolution of the culture and national sentiment of the Eastern European nations, I attempted to improve the physical and spiritual conditions of their existence; instead of destroying their personal security and human dignity, I opposed with all my might, as has been proven, every policy of violent measures, and I rigorously demanded a just attitude on the part of the German officials and a humane treatment of the Eastern Workers. Instead of practising “child slavery,” as it is called, I saw to it that young people from territories endangered by combat were granted protection and special care. Instead of exterminating religion, I reinstated the freedom of the Churches in the Eastern territories by a decree of tolerance.

In Germany, in pursuance of my ideological convictions, I demanded freedom of conscience, granted it to every opponent, and never instituted a persecution of religion.The thought of a physical annihilation of Slavs and Jews, that is to say, the actual murder of entire peoples, has never entered my mind and I most certainly did not advocate it in any way. I was of the opinion that the existing Jewish question would have to be solved by the creation of a minority right, by emigration, or by settling the Jews in a national territory over a ten-year period of time. The White Paper of the British Government of 24 July 1946 shows how historical developments can bring about measures which were never previously planned.

The practice of the German State Leadership in the war, as [ostensibly] proven here during the Trial, differed completely from my ideas. To an ever-increasing degree Adolf Hitler drew persons to himself who were not my comrades, but my opponents. With reference to their pernicious deeds I must state that they were not practising the National Socialism for which millions of believing men and women had fought, but rather, shamefully misusing it. It was a degeneration which I, too, very strongly condemned.

I frankly welcome the idea that a crime of genocide is to be outlawed by international agreement and placed under the severest penalties, with the natural provision that neither now nor in the future shall genocide be permitted in any way against the German people either.Among other matters, the Soviet prosecutor stated that the entire so-called “ideological activity” had been a “preparation for crime.” In that connection I should like to state the following: National Socialism represented the idea of overcoming the class struggle which was disintegrating the people, and uniting all classes in a large national community. Through the Labor Service, for instance, it restored the dignity of manual labor on mother earth, and directed the eyes of all Germans to the necessity of a strong peasantry. By the Winter Relief Work it created a comradely feeling among the entire nation for all fellow-citizens in need, irrespective of their former party membership. It built homes for mothers, youth hostels, and community clubs in factories, and acquainted millions with the yet unknown treasures of art.

For all that I served.

But along with my love for a free and strong Reich I never forgot my duty towards venerable Europe. In Rome, as early as 1932, 1 appealed for its preservation and peaceful development, and I fought as long as I could for the idea of internal gains for the peoples of Eastern Europe when I became Eastern Minister in 1941. Therefore in the hour of need I cannot renounce the idea of my life, the ideal of a socially peaceful Germany and a Europe conscious of its values, and I will remain true to it.

Honest service for this ideology, considering all human shortcomings, was not a conspiracy and my actions were never a crime, but I understood my struggle, just as the struggle of many thousands of my comrades, to be one conducted for the noblest idea, an idea which had been fought for under flying banners for over a hundred years. [IMT Transcript, 21 August 1946]