Such and similar cares could have motivated the wartime prime minister at the time. But there is another, later statement from Churchill that seems to confirm that his overloud protest in Teheran was what Stalin had immediately assumed it to be, a fit of histrionics unleashed by brandy.

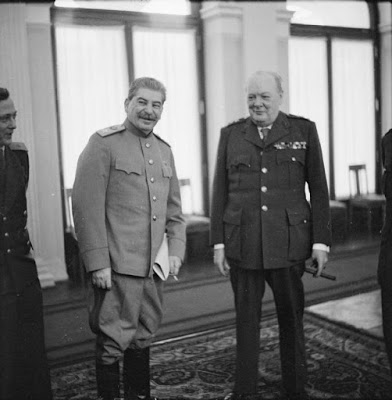

The contradiction between judicially cloaked revenge in the form of a victors’ tribunal, and an indiscriminate mass-execution such as occurred at Katyn, at first remained overt. It crops up again on 9 February 1945, on the sixth day of the Yalta Conference. There, after the Moscow Declaration of 1 November 1943, finally the practical implementation was supposed to follow. Stalin’s influence had increased greatly since Teheran. In Yalta now Churchill approaches Stalin cautiously and says something to assure him that his protest at Teheran had been theatrical bluster:

“Originally I was in favor of making a list of the main war-criminals, to identify the specified persons after their capture, and then simply to have them shot.”

(This fact is confirmed yet again in the recent book by Arthur Conte, Yalta, ou le Partage du Monde (1964). Already during this conference at Yalta, Churchill required that a list be compiled of the main war-criminals who should be shot immediately without a trial.)

Now however, Churchill affirms to his “comrade” Stalin that he has in any case reverted to the Moscow Declaration [on Atrocities] that he himself had edited, thus to the preparation for a trial. Stalin does not remain inflexible. By now he has perceived that it would be possible to make some concessions to Western prepossessions without necessarily giving up his own plan of extermination.

As soon as Stalin could get control over German “Nazis,” by which he meant, above all and quite unabashedly, German officers, he initiated his usual swift procedure. Already on 15 December 1943, two weeks after Teheran, three captured German officers were interrogated for show and then publicly shot.

It did not always necessarily happen so ostentatiously. Thousands were liquidated quietly, or died in the so-called prisoner-of-war camps, the destructive function of which, since Stalingrad, should no longer be in question. Roosevelt wanted to have 49,500, Stalin 50,000, and the younger Roosevelt hundreds of thousands shot en masse without trial. The Red dictator, however, had exceeded these figures with his death-camps long before the plan for a gigantic show-trial against defenseless captives could become reality in such a way as to combine both, the “democratic” and the Stalinist methods.

Shylock as Judge, by Heinrich Haertle — part 5

In this installment Churchill shows that he was not really so concerned with “the British concept of justice” after all.

Churchill Dissembles

From Freispruch für Deutschland by Heinrich Haertle

Translated by Hadding Scott, 2015