I. Clear communication about fundamental principles is the prerequisite for political unity.

A noteworthy point about Goebbels’ presentation is that it contains no reference whatsoever to race as such. Goebbels seems to be above all interested in the unity of the German people.

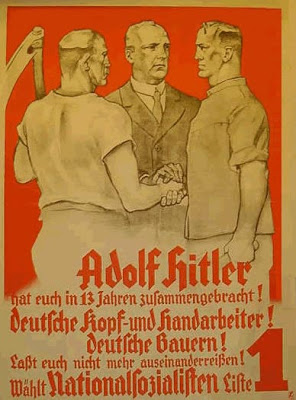

“Adolf Hitler in 13 years has brought you together! German mental and manual laborers! German farmers! Don’t let yourselves be divided anymore! Choose National-Socialists, List 1.”

Essence and Form of

We do not want to consider the entire phenomenon of national-socialism but to explain the fundamental concepts of national-socialist thinking, to reveal and delineate those pillars of thought upon which the edifice of our worldview rests, and from these fundamental concepts to derive not only the possibility but the necessity of the national-socialist reality [Realität].

Like every great worldview, national-socialism rests on a few fundamental principles that possess a deep inner meaning.

The simple explanation of all fundamental errors in the past 14 years of German politics lies in the fact that we Germans never sort out for ourselves our questions of destiny, neither as individuals nor as an organization or party. Of course concepts were discussed; it was however impossible from the start to reach unanimity about the fundamental principles of our political thinking, since every individual derived for himself the right to see something different under these concepts. What one understood as “democracy” another regarded as “monarchy”; one said, “black, white, red,” while another said, “black, red gold”; what one conceived as an authoritarian state, another saw as a “parliamentary system.”

We have discussed these concepts and talked ourselves red-faced. Had one taken the trouble 14 years ago at the beginning of the political discussion to clarify and establish these political concepts, what the individual really understood by “democracy” or “monarchy,” by “system” or “authoritarian state,” it would have been obvious that we Germans were indeed unanimous about the fundamental principles, but that we applied different names to them.

National-Socialism has now unified the thinking of the German folk for us without leading back to primitive archetypes [Urformen]. It has reduced the processes of politico-economic life, complicated in themselves, to their simplest formula. This resulted from the natural consideration of how to lead the broad masses of the folk back to political life. In order to find comprehension among the masses of the folk, we deliberately conduct a folk-oriented propaganda. Thus have we dragged onto the street facts that otherwise were accessible only to a few specialists and experts, and hammered them into the brain of the little man; all things were presented so simply that even the most primitive understanding could absorb them. We refused to operate with vague, watered-down, and unclear concepts, but rather stripped bare the meanings of all things.

Here lay the secret of our successes.

The bourgeois parties felt in their incomprehension that they were exalted above our “cult of primitivity.” With an elite-intellectual arrogance they sat above us as a court, and came to the false verdict that they were the statesmen and we were the drummerboys. At best they regarded us as agitators and pioneers of their bourgeois worldview. We, however, had other goals in mind than to conquer the teetering throne so that after the victory we might hand it over generously to them.

Since we possessed the ability to see and portray clearly the fundamental principles of the German situation, and of the life of the German community, we also had the power to move the broad masses of our folk toward these newly observed principles and fundamental formulas of political life. This pure process of agitation remained on the plain of power-politics1, not without incisive results.

I see in this success the basis for a political understanding, of the Germans and their whole folk2, with the partly democratic3, fascist, or bolshevik states. If we do not apply everywhere the same method of concept-clarification, agreement is rendered impossible.

The first necessity of every political discussion rests in this delineation of concepts and explanation of principles, and it is important that one be able to anticipate political praxis from the cursory “definition” without difficulty.

Once anybody clearly recognizes the fundamental concepts, he sees with astonishment that political praxis almost organically, naturally and self-evidently results from them. It becomes obvious to him in which direction political evolution had to lead and therefore that the process that has played out in Germany since the onset of the National-Socialist Revolution also cannot be considered as finished but must be moved forward, that it can only come to an end when the national-socialist way of thinking has renovated and filled with its content all public and private life in Germany from the ground up.

Revolutions from above generally happen very quickly. A handful of generals or statesmen form a pact, cause the regime to fall, and take over the power.

Revolutions from below by contrast grow from the depths; they evolve from the smallest primordial cells of the folk; out of ten revolutionaries grow a hundred; from a thousand, a hundred-thousand, and in the blink of an eye, when the dynamic power of the revolutionary opposition is stronger than the gradually rejected apparatus of state, the revolution has been spiritually already won. With the acquisition of power and the marriage to the apparatus of state it reaches fulfillment, which we since 30 January 1933 have experienced in Germany. Taking power is not the “revolution” in itself, rather the last part of a revolutionary act.

Visibly, the legal standard, mode of thinking, and dynamic of the revolution — grown upward in decades from the deepest roots of the power of the folk — is transcribed onto the state.

Worldview is — as the word already says — a specific manner of viewing the world. The prerequisite for it is that this manner of viewing always occurs from the same perspective. As a representative of a worldview, one does not apply different standards to economics than to politics, since cultural life stands in organic interrelation with social life, and foreign policy is considered in organic connection to the domestic political situation. Worldview means always to consider men and their relation to the world, to the state, to the economy, to culture and religion, always from the same perspective.

This process needs no big party-platform; rather it can usually be defined in a short sentence. Of course it matters whether this sentence is true or false. If it is correct it can be the salvation of a folk for several centuries or millennia; if it is false, the system that proceeded from it must fall very soon. From these early signs all great revolutions of history have proceeded. Never did a book or an initialed party-platform stand at the beginning of a revolution, but instead always only a single slogan that cast its shadow over all public and private life.

Previously the bourgeois world in Germany jeered: “The program of National-Socialism means no program.” We National-Socialists by contrast felt that we were not church fathers but agitators and pioneers of our doctrine. We had no intention of justifying our worldview scientifically, but of actualizing its teachings, and it should remain the privilege of later ages to have praxis as the knowledge-object of the Idea.7

It should never be the assignment of jurists at the green table to determine the folk’s ways of life. Conceptions that are created on paper never give the conception to a folk. Nature goes beyond science and orders her own life. Thus did it happen also in the National-Socialist Revolution!

Scholarship has only the right to interpret a new legality from what already exists, and therefore the law is conditional, resulting from the transcription of our National-Socialist revolutionary legality onto the state. It constitutes the new state of normalcy for the folk and places itself beyond scholarly criticism. The revolution has become reality and only insane reactionaries can believe that any of what we have created can be undone.

If democracy granted to us democratic methods in times of opposition, so indeed must it have happened in a democratic system. We National-Socialists however have never claimed to be representatives of a democratic viewpoint; rather we have often declared that we merely made use of democratic means in order to gain power, and that we would ruthlessly deny to our opponents all the means that had been afforded to us. Nevertheless we can declare that our government corresponds to the laws of an ennobled [veredelt] democracy.

No — these men brought back from the trenches a new way of thinking. They had experienced in the terrible needs and dangers a new kind of community that never could have been granted to them in happiness. They had learned and experienced the sovereign equalization of death, so that finally only the values of character still continued to exist. At the front, property, education, or a noble name did not matter. No distinction altered the course of bullets that cut down exalted and humble, poor and rich, big and small for eternal equalization. Among men only one single distinction continued to exist: personal merit. Never could the uniform make them equal if one was brave, the other cowardly, if one conducted himself as a man and threw his life into the fieldwork while the other tried to shirk.

It was self-evident that this evaluation would carry over from the trenches into the homeland and that the old “statesmen,” who had remained at home and had no inkling of this new attitude, would reject it. But it was only a question of time until, according to the law of force, the younger, harder, more courageous must vanquish the older and more lacking in courage.

It became obvious that even the poorest folk-comrade was devoted to his nation, although he had never been conscious of it as his property. He knew nothing about the cultural merits of his country; he knew the names Wagner, Beethoven, Mozart, Goethe, Kant, and Schopenhauer from hearsay at best. He would have been right to say, “The mines and quarries that we want to conquer mean nothing at all to me, since presumably it will be completely irrelevant for me whether I work for a German or a French owner.” Nevertheless one experienced that these men committed themselves to an ideal that, in its broad outlines, they didn’t know at all.

There, real men stood at the helm, brutal powerseekers totally unencumbered with sentimentality and remorseless in the use of armed forces. They did not let their parliaments spend weeks debating whether a mutinous sailor should be shot; rather they had the nerve to shoot the culprit.

We Germans won the war from a military perspective, but we lost all along the line politically. We had no war-aim and conducted no global politics. For a muddled confusion of vague war-aims the prole was expected to risk his life. And so it happened that our front melted, our folk fragmented, and the concept of the folk-state had no permanence before the hardness of historic unfolding; after an heroically and courageously conducted war the frightful catastrophe necessarily burst upon us. The upright, the best, the German patriots of the deed doubted the future of their folk in those gray November weeks, and many of them perished.

We National-Socialists have labored for years making clear to our folk the complicated facts of the enemy’s methods of enslavement. Today in Germany every child in school knows the frightening effects of Versailles and there is no longer any German who is not in the clear about the impact of the tribute-treaty. But 15 years ago the mutinous German chancellor could step before the nation and regarding this disgraceful treaty memorialize the utterance: “The German folk has been victorious all along the line!”

What a change has been accomplished in these 15 years of struggle. One can in fact say: peoples are not always the same; all propensities for good or evil lie in them and it depends always on their leaderships whether nations resolve for good or evil! The German folk of today must not be compared with that of 1918, just as little as the masses of 1918 can be set in comparison with the nation of 1914. Here we are dealing with fundamentally different mentalities, with a different mode of thinking, a new sense of community and a closer cohesion.

National-Socialism means National Unity

The socialist is elevated above that. He stands on the position: We must all become one folk so that the nation can withstand its crisis. Every sacrifice is right for becoming a folk. I belong to my folk in good and in bad days, and I bear joy and suffering along with it. I know no classes; rather I feel myself purely and simply committed to the nation!

______________________________

1. What could Goebbels possibly mean by this? Machtpolitik refers to foreign relations; surely the NSDAP did not focus its electoral propaganda entirely on that.

2. ihres ganzen Volkes — probably referring to Volksdeutsche, the millions of ethnic Germans outside of Germany, e.g. in Poland.

3. mit den teilweise demokratischen … Staaten — What is Goebbels getting at by qualifying “democratic” with “partly”?

4. irgendwelcher Machtmittel — Such “instruments of power” in several examples that I find refer to armed forces, usually belonging to a government, although it can mean other agencies of government.

5. e.g., Mussolini’s march on Rome and the Beerhall Putsch.

6. The Green Table was a ballet by Kurt Jooss that debuted in Paris in 1932. It portrayed politicians as making decisions without regard for how ordinary people would be affected, specifically the decision to fight the First World War.

7. Erkenntnisobjekt der Idee. Philosophical language. Goebbels seems to be invoking the Hegelian concept of progress in history, wherein an idea that dominates an epoch is at first expressed unselfconsciously, and only later after it has some history behind itself, and is able to contemplate its own actions, is it able to explain itself. The implication is that it was unreasonable to expect the new idea of national-socialism to explain itself thoroughly in advance.

8. Weltvolk, “people of the world,” can connote either a people with an empire like the English or a people scattered about the world like the Jews. There may be a some sense of superiority in asserting that the Germans had never been a Weltvolk.

10. A line from the Roman poet Horace, Ode III.2.13: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.