The broad outline of Bardèche’s view of Mussolini is intuitively obvious. Clearly, Mussolini accomplished good things for Italy, and then, at some point, became unrealistically ambitious. How much more fortunate Fascist Italy would have been if the temptation of an opportunistic entry into the Second World War, at a moment when France was already on the verge of defeat, had been resisted.

Since I know little about Mussolini, I can only accept what Bardèche says about him. Regarding the next section, about Hitler, I shall have some points of contention.

I omit the first few paragraphs of this chapter, where Bardèche argues that he as a fascist does not have to approve everything that a fascist has ever done. That point should be self-evident.

… The first version of fascism that contemporary history presents to us is Italian Fascism. Originally, it is a movement of socialist activists and veterans that saves Italy from Bolshevism.

Mussolini’s mother was a schoolteacher, and his father was a blacksmith who was an activist for the Communist International. Mussolini was imprisoned at the age of twenty for having fomented a general strike. He is initially defiant, takes up exile in Switzerland, translates Kropotkin; the first periodical that he founds is called La Lotta di Classe (The Class-Struggle); the first daily newspaper that he manages is a socialist newspaper. The beginnings of Fascism are consistent with this origin. The speech at San Sepulcro, which is the birth-certificate of the fascio, proclaims the confiscation of the property of the newly wealthy (nouveax riches), the dissolution of the large secret societies, the redistribution of land, the participation of workers in the management of businesses, and the suppression of titles of nobility.

In twenty years, what from this program did Fascism fulfill? What we can say, what we must say, is that it was something else. Very quickly, Fascism forgot a large part of its revolutionary program in order to accomplish a work of practical efficiency and unity. It had come to power to avert anarchy, chaos, civil war. It acted with great urgency to reestablish order, work, peace. Then it organized and constructed. Italy became again the nation of builders. The Roman sap once again flowed in the old tree-trunk. Mussolini was initially a proconsul. Fascism produced roads, hospitals, schools, aqueducts; it drained marshes; it increased the harvests. “Asfaltar no es gubernar” [1], was one reaction. But it also governed. Mussolini established corporatism, an achievement requiring much more finesse than an Autobahn. The Charter of Labor was certainly not the echo of the speech at San Sepulcro. But it realistically laid the foundations of a socialist city that the future could expand: the replacement of parliamentary assemblies with union-meetings (instances syndicales), the representation of workers, collective contracts, social security, organization of leisure-activities, were so many beginnings that a will for socialist management could develop and transform. There was however one essential condition. Since Fascism wanted to maintain private property while imposing its will on the selfishness of liberal capitalism, it was necessary to know that the Fascist state found itself faced at every moment with surreptitious opposition, and that it was committed to perpetual vigilance.

This was thus the youth of Fascism and I confess that I cannot think of it without nostalgia. There were black shirts and boots, lictors and raised arms, but without anything raucous and colossal. Mussolini was barely guarded. He loved the people, the children, informality. He was easily accessible. Sometimes, he took his red car — which he drove, it was said, quite badly — and departed alone to wander in his province of Italy more simply than a Laelius or a Scipio ever had. He was beloved. “You are all of us,” was said to him. The slogans had not appeared on the walls and it was not an article of faith that Mussolini was always right. It was a “popular dictatorship,” said the Fascists themselves, words with a bizarre resonance today. It was the time when Mussolini wore white gaiters and a bowler hat. I quite love this touching period.

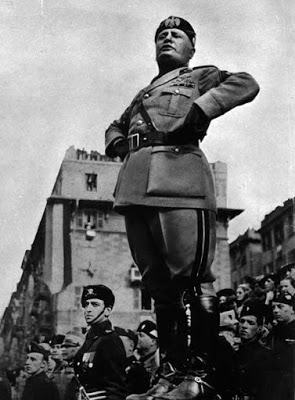

The Fascist style came only later, with its uniforms, its emblems, its inscriptions, its heel-clickings, and its chief portrayed with fists on hips and chin high. These military forms of discipline symbolize the unity of the nation. They make the nation feel its own strength; they intoxicate it with effectiveness, with energy; they promise to it manly action; they speak to it about honor and sacrifice. Through them, man escapes his mediocre and routine life, from the joyless function that he humbly performs in the city; he becomes a soldier at his post; his life has a meaning; he is united with the other men of his nation as a soldier is united with his comrades. Traditional Fascism recognizes itself in the parades of these young heroes who are quite hard, quite uncompromising, who can also furnish at once, as blind destiny demands, martyrs or butchers, brutes or saints. The struggle against power, the struggle to prevent nations from dying, cannot do without these phalanxes, I know. Always the suit of lights.

But if the very life of the nation is based on this military civic-mindedness, how

dangerous it becomes! Mussolini, having become Duce, declared infallible, no longer appearing except on the balcony like a pope, accompanied by dignitaries who come to a halt six paces in front of him, loses in my eyes all the charm of the little socialist

schoolteacher who had become his people’s guide. And above all, he is no longer the people’s guide that he was. The splendor of majesty, the habit of performance, separate him from men. He no longer knows Italy except through spectacular tours and the reports of prefects. This consul, in the midst of ovations, condemns himself to being no more than a bureaucrat. The dignitaries of Fascism are his eyes, his hand, his lictors. And if these men are idiots? If the distance becomes greater each day between the real country and the idea that the helmeted army maintains in the mind of the dictator as it passes under his windows singing?

The catastrophe of Italian Fascism had perhaps no other origin. Mussolini, irritated by the sanctions, was dreaming of an Italy that would be military, Roman, helmeted, invincible. He heard the footstep of the legions. And the footstep of the legions echoed, in fact, under his windows; his praetors were showing the locations of his camps to him on maps. He spoke of the “warrior nation” and, as a consequence of speaking about it, he believed in the “warrior nation.” He forgot the charming Italian people and the mandolins of Naples and the hardworking craftsmen of Italy and its immense poor lands and the steaming soup on the table of the family that awaits the children in the evening. He was beholding a dictator’s dream instead of the face of Italy. And he was forgetting also that social justice is a battle that is won each day, that it demands an infinite love and infinite attention, that there is need of constant monitoring to defend the workers against the rich, and that one cannot rely on the reports of prefects.

Lost in his dream of grandeur, he played with the shadow and forgot the essential. As emperor of a phantom nation, he presses buttons that activate nothing. But finally, as Lieutenant Bonaparte at Montereau and Champaubert[2] nearly saved the success of Napoleon, it is the little socialist schoolteacher who miraculously came to the aid of Mussolini the dictator.

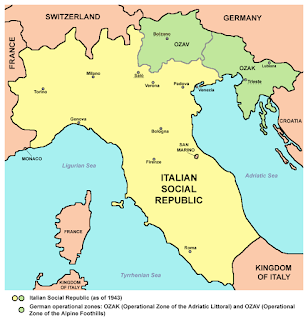

Nothing is more moving in the history of Italian Fascism than the return to roots accomplished under the iron fist of defeat. The program of the Salò Republic in 1944 is that upon which Mussolini ought, twenty years earlier, to have staked his power and his life. That is the true Fascism. But, like the battles of the French countryside, it came too late. There is a moment when no wisdom can any longer stop the avalanches caused by mistakes. Mussolini died of his caesarism, of the isolation that caesarism brings, of the delusions that it allows to develop, of the optimism and the easy satisfactions with which it contents itself, of the stardust that it casts into the eyes of others, and that finally blinds it. Italian Fascism was possessed by the ghost of Rome: in this intoxication with history, it lost touch with reality. We must learn that fascism cannot content itself with being a caesarism.

___________________

[1] To pave is not to govern. This was actually said, not about Mussolini but about Franco, by Salvador de Madariaga, a Spanish expatriate who lived in England and enjoyed high status there as a proponent of liberalism.

[2] These were among Napoleon’s last battles, in February 1814, wherein he made efficient use of his small force against much greater numbers. The performance in these last battles, although excellent, was not sufficient to win the war and prevent Napoleon’s exile to Elba.