Nulla poena sine lege, an axiom constantly recurring in our old English books, is as ancient as the Quaestiones Perpetuae. In the later Roman jurists it is thus expanded: Nullum delictum, nulla poena sine praevia lege poenali.

In the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg this is particularly important in regard to the accusation of “waging aggressive war,” which had never been considered a crime under international law. This in fact had been pointed out at the London conference where the charter for the tribunal was established, by the French delegate, Dr. André Gros.

The argument against ex post facto law has no bearing whatsoever on any accusation about gassing Jews, since a specific accusation like that could have been prosecuted under Germany’s own laws against homicide. Never was it made legal in National-Socialist Germany to kill Jews without provocation.

|

|

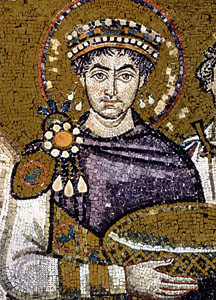

| Justinian I |

At first, the defense-attorney Dr. Stahmer had to accept the taboo-declaration of the “high court.” In his pleading for Reich’s Marshal Goering however he repeats his attack and renews his argument to the judges and prosecutors against the legal foundations of the proceedings. He dares to demonstrate to the tribunal that even National-Socialist legislation essentially retained the principle: without law no punishment. The Third Reich issued no retroactive laws, but merely applied existing laws with increased punishment. Even this state did not dare to violate the legal principle: nulla poena sine lege praevia.

Precisely the liberal worldview of the signers of the charter would require them to treat the legal principle nulla poena sine lege praevia as especially sacred, Stahmer stresses:

“This is also apparent of course in the fact that the [Allied] Control Council for Germany has newly impressed this principle upon all Germans most acutely by removing analogy again from criminal law, in §2a of the criminal code.”

All the more incomprehensible is it for the German sense of justice when this principle now is not supposed to be valid toward Germans, who are accused here. To the French prosecutor he counters that one cannot begin to strengthen the idea of law by violating it. He admonishes the English chief prosecuting attorney that he himself had called ex post facto legislation one of the most abominable doctrines.

He attacks Jackson even more sharply. He poses the question:

“May a criminal court that wants to effect justice apply concepts of law that, to the accused and to their people’s legal scholars, are entirely alien and always have been alien?”

Attorney [Gustav] Steinbauer, Dr. Seyss-Inquart’s defender, also opposes with total resolve the construction of retroactive laws. He cites the American weekly periodical Time, which on 26 November 1945 attacks an essential element of the tribunal’s legal fictions:

Whatever kinds of laws the Allies attempt to set up for the purposes of the Nuremberg Tribunal, most of these laws did not yet exist at the time when the deeds were committed. Punishment ex post facto has been condemned by jurists since the days of Cicero.

The French national assembly too, on 19 April 1946, thus exactly three months previously, had affirmed in Article X of the Charter of Human Rights:

Law has no retroactive force. No one can be condemned and punished except in accord with law that has been proclaimed and published before the deed to be punished….

On 25 July 1946 the defense-attorney for Rudolf Hess, Dr. [Alfred] Seidl, also attacks the abuse of beginning a renovation of international law with such questionable means: it must have unforeseeable consequences if a principle is violated that is an integrating component of international law – the principle that an action can only be punished when its punishability had been specified in law before the action was committed. A violation of the principle nulla poena sine lege necessarily makes the idea of law in general questionable, he said.