W.M. Bevis was a psychiatrist at Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., where he presumably had extensive experience in treating Negroes. This article for the American Journal of Psychiatry (1921) summarizes his observations about mental peculiarities of the Negro.

The Negro race evinces certain phylogenetic traits of character, habit, and behavior that seem sufficiently important to make the consideration of these peculiarities worthwhile; especially as these psychic characteristics have their effect upon and are reflected in the psychoses most frequently seen in the Negro. Forming so large a part of the population and living as he does under conditions, climatic and otherwise, that are favorable and natural, the Negro of the Southern states forms the basis of the observations and deductions of this brief article.

Less than three hundred years ago the alien ancestors of most of the families of this race were savages or cannibals in the jungles of Central Africa. From this very primitive level they were unwillingly brought to these shores and into an environment of higher civilization for which the biological development of the race had not made adequate preparation. In later years, citizenship with its novel privileges (possibly a greater transition than the first) was thrust upon the race finding it poorly prepared, intellectually, for the adjustment to this new social order. Instinctively the Negro turned to the ways of the White man, under whose tutelage he had been, and made an effort to compensate for psychic inferiority by imitating the superior race. Thus we see in this people a talent for mimicry that is remarkable. Efforts to imitate his white neighbors in speech, dress, and social customs are often overwrought and ludicrous, but sometimes sufficiently exact to delude the uninitiated into the belief that the mental level of the Negro is only slightly inferior to that of the Caucasian.

The insidious addition of White blood to the Negro race has produced significant effects upon the latter. This racial admixture of blood has been between the Negro female and the White male, with practically none between the Negro male and the White female. But we cannot agree with Hoffman when he says that there is probably no true-blooded Black man in the United States today. A limited observation and study of the Negro families in the South will reveal the fact that there are still hundreds of the pure Black African stock untouched by any possibility of miscegenation, though as the years go by they are passing. If the original White parent were always even an average representative of his race, mentally and morally, the hereditary effect upon the more or less mulatto offspring would naturally be that of improvement of the traits and mentality of the colored race, but unfortunately the White man by whom this fusion of blood starts is most often feeble-minded, criminal, or both. “This miscegenation appears to have effected the longevity of the race, and the changed social environment has brought about a moral and mental deterioration, together with a diminished power of vital resistance. Information has been brought out by some writers that the mulatto more nearly approaches the White in the contour and shape of the cranium; that the facial angle in the mulatto is larger than in the Negro; that the cranial capacity has been increased, but that the race may have gained in an intellectual way but not in a moral.” – according to O’Malley.Healthy Negro children are bright, cunning, full of life and intelligent, but about puberty there begins a slowing up of mental development and a loss of interest in education as sexual matters and a “good time” begin to dominate the life and have the first place in the thoughts of the Negro. From this period promiscuous sex relations, gambling, petty thievery, drinking, loafing, and a carefree, prodigal life, full to the brim with excitement, interspersed with the smallest possible amount of work, consume his time. The female of the race begins promiscuous heterosexual relations, even with grown men, at a remarkably early age, resulting in illegitimacy and the spread of venereal diseases. Many mulattoes do not conceal their pride in being the paramour of a White man or becoming the mother of a quadroon. With their low moral level and as free agents, no wrong is felt in gratifying their natural instincts and appetites. The untoward effects of their excesses and vices are potent factors in the production of mental diseases.

Motion, music, excitement, or a combination of these make up much of the life of colored people. Their natural musical ability of a peculiar type, and their sense of rhythm, are too well known to make comment necessary. Motion pictures especially delight but the modern dance has little or no charm for them. The “cake walk, shuffling, strutting, buck and wing,” and such dances as give a wide range of motion of the arms, legs, and feet, suggestive of dances and orgies of the original African tribes, are executed in great style.

Naturally, the Negro lacks initiative; takes no thought for the immediate future, living only in the present, without recalling with any degree of concern the experiences of the past and profiting by the same; does not worry [about] poverty or failure; distrusts members of his own race, and shows little or no sympathy for each other when in trouble; is jolly, careless, and easily amused, but sadness and depression have little part in his psychic make-up.

All Negroes have a fear of darkness and seldom venture out alone at night unless on mischief bent. Even when two or more are out together there is always fear and much caution. This noctiphobia is closely associated with the superstitions of the race, is akin to actual cowardice, so easily demonstrated, and emphasized by the constant reiteration of stories of the ante-bellum system of patrol of the plantations, of ghosts and impresive nocturnal performances of the Ku Klux Klan.

It is the conscious or unconscious wish of every Negro to be White. This is brought out in his dreams, the hope of being a white and snowy being in the eternal life, and in psychoses in which he is or was white.

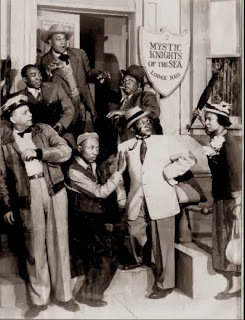

Quasi-Masonic lodge in Amos & Andy. Very dear to the heart of the whole race is the privilege of belonging to a secret order. The more lodges to which he belongs, the greater citizen he is considered. The secret work with its mysticism, ceremonies of initiation, parades and marches in highly colored uniforms and regalia on holidays or on funeral occasions greatly fascinate and attract both the men and the women.

The religion of the race is unique in that it is not taken as seriously as is superstition. It is difficult to determine where one ends and the other begins. Original tribal worship, the queer racial awe of the mysterious, and associations with the White race have affected their religion. Prior to emancipation, the slaves attended the churches of the planters, occupying galleries especially prepared for them. Doctrines thus inculcated formed the background for their religious activities of later years. To these have been added such sounds, motions, and residual forms and ceremonies as have been left them by their African forefathers in efforts to appease the wrath and do honor to many deities. From time to time are added features that have proven successful in religious matters by their White friends. In their religious services, whether it be in singing, prayer, testimony, or sermon, there is always a varying accompaniment ranging from an occasional grunt, groan, or exclamation to an almost continuous volley of all these, with continuous motion by the congregation, increasing in volume as the service progresses until a point is reached where their emotional fervor reaches its climax in wild disorder. During a single service a congregation of colored worshippers may work themselves into an hysterical state of emotional exaltation in which “the real world disappears from sight and the supernatural alone exists for them.” Behavior at these times appears to be only a step from the manic phase of manic-depressive psychosis or a catatonic excitement. The service is never complete until a reaction from this state back to comparative quietude takes place. Meetings often last five or six hours and continue every night for several weeks. Sermons and exhortation delivered and received with such emotion and enthusiasm bear little or no fruit in their everyday life and conduct, affecting favorably the morals of very few.

Nothing in the life of the Negro stands out more prominently than his superstition. It influences his thought and conduct more than anything else. In no other trait or peculiarity do we find more plainly the imprint of primitive African life and customs. A monograph might be written describing and tracing the origin of this psychic weakness of those of “ebony hue” but we mention only the most common and strongly believed superstitious ideas, born as they are of fear, credulity, intellectual poverty, and childlike imagination. Even the most talkative of the race are reticent and ashamed to talk about their superstitions, and make great effort to conceal all traces of it in ordinary conversation. It is best understood by hearing conversations between individuals of the race when they think it impossible to be heard by a White person. Under these circumstances they discuss what they have heard and believe and match experiences freely with each other. Frequently this trait comes to the surface in delusions and obsessions but is even then disclosed with reserve.

Buried deep in the nature of this people is the belief that souls wander around not far from the interred body during twilight and at night as spirits, ghosts, or “hants,” to trouble and disturb the peace of mind of those who have been unkind to the deceased when living. This belief and fear are sufficient to occasionally bring about optical illusions, especially if the moon is shining just a little, that are always without question taken as “hants.” It is also believed that the left hind foot of a rabbit found in a “graveyard” is a charm or “fetich” that will make them successful at dice and in many ways ward off misfortune. Teeth of animals, snake rattles and skins are said to possess magic power of protection. Great faith is placed in witchcraft, palmistry, and divination. Persons who claim power to give information about the future, as in the fortune-telling of these fakers, are considered great and all-wise representatives of the “Most High,” especially if they present a weird appearance, use words that are difficult to pronounce and hard to understand, and do some sleight-of-hand tricks. The moon, particularly a new or waning moon, is ever to the colored man a sign of time and a reminder of death. This “time of the moon” is considered unfavorable for any doubtful or dangerous undertaking. It is also unlucky to start on an errand and turn back, but if such must be done, it is necessary to make a cross-mark on the ground and spit in one of the angles. Of interest to the psychiatrist is the belief in the ability of certain members of the race to “conjure” or place a “hoodoo,” “voodoo,” or “spell” upon another. The victim things that his enemy uses this power very secretly at will and for his own benefit. All sorts of bad luck, persecutions, disease, and mental conditions can be called down upon the person who is under the spell. This unfortunate condition can only be relieved by the intervention of some person having a greater power to “conjure” than the original enemy. Persons supposed to possess great power to break these spells and to ward off the evil operations or the power of the enemies are referred to as “Witch Doctors,” or as “Night Doctors,” and are held in great reverence. Parents of a young patient having a psychosis often contend that all that is wrong is that he or she is suffering from a “spell” placed on by a jealous or disappointed lover. The colored patients themselves often give being under a “spell” or “hoodoo” as explanation for their mental difficulties. They will often say, “He controls my mind.” “Love Powders” to change one’s luck in winning the affection fo a person of the opposite sex or to break the power of a rival are much in demand, if guaranteed. With all the handicaps resulting from fears, low ideals, and primitive notions, it occasionally happens that the Negro youth is fortunate in having the proper guidance and sufficient work to prevent him from making a complete wreck of his physical and mental life. Spurred on by a good example and a wholesome desire to be an exception and a leader who can help the race, many profit by the opportunities offered even in the South to secure a good education and develop into most excellent citizens.

After this, Bevis discusses forms of mental illness that are prevalent among Blacks, comparing their occurrence among Whites. Blacks suffer from schizophrenia much more than Whites.

This is not surprising when their racial character make-up and the atmosphere of superstition in which they move are considered. Much of their usual behavior seems only a step from the simpler types of this classification. The catatonic form predominates, occurring almost twice as often as among White patients.

Alcoholism and suicide, says Bevis, are rare among Negroes.*

If we consider the psychoses of the Negro from the mechanistic viewpoint, it will be found that practically all may be correctly included in the following classes, named in the order most frequently observed: dissociation, compensatory, and repression. Most of such psychoses are benign and acute, but may become chronic if improvement does not relieve the situation in time to prevent it. The most common causative factors in the dissociation types are: “inability to prevent repressed disguised cravings from breaking through the ego’s resistance,” as mentioned by Kempf; toxic elements, and real or imaginary domination by others. Conflicts or situations becoming almost unbearable, with no suitable means of sublimating or otherwise avoiding, make a psychosis of this character an easy avenue of escape from the field of reality. An example is the case of a woman who was under the influence of a “spell” put ipon her by another, committed a crime, asserting that it was not she that did it but that under this uncontrollable influence she became the helpless agent.

Fear is the all-pervading cause in the compensatory type, “fear of fear, fear of sexual impotency, and fear of loss of the love-object” being the most noticeable elements. These manifest themselves in grandiose, unreasonable claims, persecutory ideas, and pathological lying. An example is the case of a man, though Black, said that he was the commissioned representative of God to protect White women, and that he might be more effectual in his mission was made White, and for all these reasons has been grossly mistreated by both Black and White.

The repression type makes up the smallest part of the racial psychoses under consideration and is more of a compulsion-neurosis than a psychosis. There are phobias and obsessions suggestive of psychaesthenia. As so clearly expressed by White, “there seems to be an alternation between love and hate with no possibility of the formation of a working compromise.” This type is more often seen in those who show an appreciable proportion of White ancestry.

In our observations the following points are evident:(1) The Southern Negro has certain psychological traits that are reflected in his psychoses.

(2) Motion, rhythm, music, and excitement make up a large part of the life of the race.

(3) Naturally, the most of the race are care-free, live in the “here and now” with limited capacity to recall or profit by experiences of the past. Sadness and depression have little part in his psychological make-up.

(4) Of all his peculiarities, fears and superstitious ideas stand out most prominently.

(5) The number of cases of alcoholic psychoses is surprisingly low.

(6) Suicide and suicidal tendencies are almost absent in colored patients, the ratio being about one to three thousand in state hospitals.

(7) The incidence of cerebro-spinal syphilis and paresis is relatively low in the Southern Negro.

(8) Manic-depressive psychoses are observed to occur in higher percentage than that given by Green in 1916 (17 per cent). The manic phase is the one nearly always seen.

(9) Dementia praecox [i.e. schizophrenia] stands at the head of the list of the psychoses of the colored, catatonic form occurring about twice as often as in the White, and paranoid form coming next in importance.

(10) Mechanistic classification of the psychoses of this race show that nearly all are dissociation, compensatory, or repression types.

_____________________________________

* What Bevis wrote about the rarity of alcoholism among Blacks in 1921 is contradicted by the prevalent stereotype about Black alcoholism in 2013. But a report (R. Caetano, C.L. Clark, T. Tam, “Alcohol Consumption among Racial/Ethnic Minorities”) published by the NIH in 1998 states that the stereotype of alcohol consuption among Blacks is exaggerated, that alcohol-consumption is still more prevalent among Whites: “Results from the 1984 National Alcohol Survey showed that several sociodemographic factors (e.g., age) helped shape blacks’ drinking patterns, degree of alcohol-related problems, and attitudes toward drinking and that these influences differed from those observed among whites (Herd and Caetano 1987). For example, rates of heavy drinking among blacks were highest among men in their 40s and 50s, whereas the rates among whites were highest among men in their 20s. In the 1995 National Alcohol Survey, however, rates of heavy drinking among white men in their 20s have dropped, such that black and white men now show similar drinking patterns until they reach age 49. Moreover, in the 50- to 59-year-old age group, rates of heavy drinking are substantially higher among whites than among blacks (16 percent versus 3 percent, respectively). The causes of these changes in alcohol consumption patterns between 1984 and 1995 remain unclear. Finally, the abstention rate currently is higher among black men than among white men (36 percent versus 26 percent, respectively), further contradicting common assumptions about blacks’ drinking patterns (Caetano and Clark 1998 a). Other research also has indicated that the attitudes of blacks toward drinking and drunkenness are not overly permissive and, in some cases, tend to be more conservative than those of whites (Caetano and Clark 1998 c ). For example, many studies have documented relatively high abstention rates among black women compared with white women (Caetano and Kaskutas 1995; Herd and Caetano 1987). The results of the 1995 National Alcohol Survey further support those findings, with abstention rates of 55 percent among black women and 39 percent among white women (Caetano and Clark 1998 a ). In summary, recent research has contradicted many of the stereotypes of alcohol consumption patterns among blacks.”