|

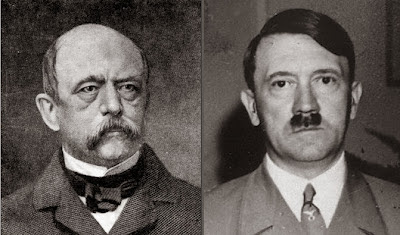

| Otto von Bismarck and Adolf Hitler pursued similar goals under different circumstances. |

by Dr. Johannes Stark

II. The Leader

All progress and all culture of humanity are not born from the majority, but rely exclusively upon the ingenuity and drive of the personality.

Hitler

The cause for which we fight is the securing of the existence and the increase of our race and our people, the nourishing of our children and preservation of our blood, and the freedom and independence of the Fatherland, so that our people can mature for the fulfillment of the mission assigned also to it by the Creator of the Universe.

Hitler

The following explanations are meant not to treat Hitler’s goals and personality in their entirety as can be expected from a historiographer; mainly because the available space would not suffice for that. Rather there are in them only those aspects of Hitler’s personality, and such particular goals elucidated by him, as are likely to interest a certain circle of readers.

In the last years I have spoken with many capable, generally academically educated men from all professions about Hitler and his movement: with government officials from ministers to inspectors in a foreign office, from a general director of an economic-group [Wirtschaftskonzern] to the manager of a factory, from a university-professor to a public school teacher. These were men of great, in some cases exceptional competence in their fields and professional circles, of nationalist outlook and nationalist desire. Almost all however rejected Hitler and his movement. It was quite disturbing for me to have to conclude that these German men based their opinion of Hitler not on an accurate knowledge of his previous work and his writings: instead for the most part they contented themselves with a slogan from the anti-Hitler press. And whenever I explained to them in no uncertain terms that they were in gross ignorance about Hitler and his goals, and that they should have at least read his book before so casually judging the greatest and most promising personality in the German nation, they would shake their heads and lament that they had no time for a matter that would surely soon die out.

Today, after Hitler’s overwhelming electoral victory on September 14th, many Germans who until then judged Hitler wrongly will be inclined or have the wish to get to know his goals and personality more accurately than hitherto, and to heed the answers that can be given to the objections against Hitler that they might raise even today.

Bismarck’s highest goals were: binding together the insular German states into a political unity in a German Reich, after that securing this Reich against its internal and external enemies.

Hitler’s highest goals are: creation of a German national community in the consciousness of all German people that they have a shared national character; strengthening of the German people in body and soul; and cultural and economic development of its assets and strengths, unimpeded by foreign peoples.

Bismarck’s next tasks for the attainment of his highest goals were: abroad, exclusion of the Habsburg Empire from the community of German states, neutralization of the western enemy of German unity [France], the Triple Alliance policy, and the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia; for securing the Reich internally, suppression of the Social-Democrats and the Center Party within Germany.

Hitler’s next tasks for the attainment of his highest goals were and are: organization of a great number of German-conscious and struggle-ready men into a party, enlightenment of the mass of the German people about its situation and its enemies through an extended hard-hitting propaganda, acquisition of a deciding influence in the Reichstag, takeover of governments and destruction of Marxism, and therewith destruction of the domestic political weapon of the international finance-Jews, this at home; abroad, overtures toward an alliance with England and Italy for the purpose of shaking off the coercion of the German people through the the international finance-Jews’ external weapon, French militarism.

Bismarck’s success and failure in the attainment of his goals were grounded in his personality. Bismarck had the gift of seeing reality and inferring from observation of particular manifestations the cause determining them; he was an idealist who placed himself at the service of his people; he was a great character who fearlessly and tenaciously struggled for his goals. From personal experience he gained a realistic knowledge of the significance of the Prussian government and army; he became familiar with the dynastic relationships in Germany, Austria, Russia, and France, and the leading diplomats in these countries. And in accord with this knowledge in his foreign policy he employed the available military forces and diplomatic influence in negotiations; thus he attained his first goal, the founding of the German Reich. But Bismarck misjudged the influence of the Center leaders that actually existed in the Catholic portion of the German people; he knew not the soul and the social needs of the German industrial worker; therefore he chose the wrong methods for securing the Reich internally; his struggle using the powers of the governmen against the Center and against burgeoning Marxism met with no success.

Hitler, like Bismarck, has the gift of seeing reality. But the territory of his experiences and observations is essentially different from Bismarck’s. While Bismarck’s eye saw preponderantly the organs of the state, namely the monarchs, ministers, parliaments, and armies, Hitler’s eye sees preponderantly the bearer of the state, the folk itself. As a child of the folk he lives in the midst of it, stands next to the manual laborer as a manual laborer, stands next to the common soldier as a common soldier, observes and collects experiences throughout many years. In Vienna as a construction worker he observes the economic and cultural misery of the folk’s lower class, the Jew in his influence upon the working class and the press, the successes of Lueger’s Christian-Social Party, the struggles of the nationalities in the parliament at Vienna, and the slavization-policy of the Habsburgs. As a soldier for four years on the Western Front he observes the soul of his comrades, the effect of enemy propaganda and propaganda from the homeland. In the homeland as a wounded soldier, he observes the effects of Jewish war-societies and the Jewish press upon the people. During the revolution he observes attentively the relationship of the revolutionaries, the bourgeoisie, civil servants, the army, and the army-associations. In the year 1923 he receives in Munich the opportunity also to become acquainted with leading politicians.

Like Bismarck, Hitler understands not merely how to see things and men as they really are; rather he is like that one thinker who recognizes the causes of the observed events and the motives of the people acting in them. But Hitler goes even deeper; he is equal to a great natural scientist who reveals the law-governed relationships of observed phenomena and penetrates into knowledge of their ultimate causes and forces. He sees well the immediate causes for the growth of the Marxist movement, for the success of subversive propaganda at the front and in the homeland, for the failure of the bourgeoisie, officers, and civil servants in the face of mutineers and revolutionaries, the causes for the establishment and tolerance until now of the disgraceful and murderous policy of compliance [with the Treaty of Versailles]. But he searches even deeper, after the ultimate root of the greatest achievements and of the ruin of a nation, and he finds it in the racial character of a people and in the ingenuity and energy of particular personalities in it.

In accord with this fundamental knowledge Hitler chooses the highest goals for the German people; from the same knowledge and in regard to these goals he also formulates the fundamental tasks for the attainment of them: the state is there for the folk; its organization has to serve the wellbeing and development [Entwicklung] of the folk; its government belongs not in the hands of the makers of a parliamentary majority but in the hands of a responsible leader; the upbringing of the youth must have as its goal the development of national consciousness and the feeling of honor and responsibility toward the folk-community, and the cultivation of a healthy soul in a healthy body. The economy of the folk is to be secured in itself through the promotion of agriculture and through the acquisition of new permanent settlement-area.

Bismarck had personal courage compared to the mass of the people and compared to his king; he had courage for the war with France; he was a master of diplomatic technique; he was an unbending fighter until his dismissal, even until his death. Of course at the beginning of his political activity great helps were available to him: a wise, trustworthy monarch, a crack army, an efficient government.

Hitler sees himself at the beginning of his political activity faced with incomparably greater difficulties than Bismarck: dissolution of the army, corruption of the government, overpowering Jewish-led internal foes, a front of militarily overpowering external foes of the German folk. No financial means and no political organizations are at his disposal. Truly, Hitler’s courage, to begin the deed of realizing his political goals under such circumstances, was even greater than the courage with which he exposed himself in his gatherings to the danger of being beaten to death by the incited mob.

Hitler’s cleverness in the choice of the practical means for the solution of great and small tasks is astonishing: he is the born organizer. He chooses and creates his means for himself according to the lay of the existing circumstances in such a way as to attain the set goal. Thus he adapted the nature of his propaganda to capture the mass of the people, above all the Marxist-led working class; he secured his party and its gatherings against the terror of his Marxist opponents through the organization of battle-loving, fearless men in a detachment of his movement, the Sturm-Abteilung (S.A.); he gave to his party a firm program and set it financially upon the secure basis of contributions from the members; he convinced all Germany with a network of local groups and bound them together tightly controlled [in einer straffen Leitung] by his hand. A crowning achievement of unification, showing deep insight with clever calculation, was his creation of a special banner for his movement, the hooked-cross flag, along with the motto: freedom and bread.

Hitler’s perseverance and unbending will in the pursuit of his goals has already proven itself in a quite dramatic form. In November 1923 the van of the procession of his fellow strugglers and supporters is gunned down by the rifles of German soldiers in front of the Feldherrnhalle in Munich: instead of the guilty and responsible Bavarian general state commissar, Hitler is put on trial; he is confined in a fortress; the Jewish press make him and his movement disreputable in the bourgeoisie and among the workers with the word putsch. But Hitler refuses to bend. Even during his imprisonment in Landsberg he writes the first volume of his book, which bears the title My Struggle. Nowhere in this book is even a whiff of flagging courage to be detected: instead, everywhere the conviction of the correctness of his goals and the certainty of the final victory of the movement that he had called to life. And no sooner is Hitler free again than he begins rebuilding his party, labors without rest and perseveres against the blackout [Totschweigetaktik] now being employed by the Jewish and Jewish-influenced press.

The statesman proves himself in the success of his political activity. Bismarck’s work lies hidden from our eyes. Hitler yet stands at the beginning of his activity. But his successes toward his highest goals are already so great that all eyes of statesmen in Germany and abroad see them. From a group of seven men Hitler has in a few years developed a party of millions. In this party Germans of all classes and denominations feel that they are a national community [völkische Gemeinschaft]; more than a hundred-thousand strong men stand ready to fend off the violation of their national community with the fist. In the Reichstag Hitler’s parliamentary fighting-force of 107 men stands as the second-strongest party. Marxism and the Jewish-led bourgeoisie have been put on the defensive by Hitler and his movement. The entire domestic policy of the government of the Reich and of the governments of the lands must reckon with the party led by Hitler; foreign policy must follow. The whole rest of the world watches Hitler and begins to reckon seriously with the present and still-increasing strength of his movement: from Italy the leader of the Italian nation greets Hitler; in England one of the most influential newspaper-owners acknowledges the significance of Hitler’s movement and the need for revision of the treaties forced on Germany; the fear of Hitler’s awakening Germany talks in the speeches of French politicians. Shortly before Hitler’s victory the Dictate of Versailles still seemed both to the French, and to the German Marxists and to the compliance-politicians, as an unassailable fundamental law for the political order of Europe and for the suppression of the German people. A few weeks after Hitler’s victory, not only is revision of the dictate of enslavement pleaded as an unquestionable necessity in America, England, and Italy, but in France itself a known German-hater gives his fellow countrymen the good advice to revise the so-called peace-treaty for Germany’s benefit as soon as possible. And in Germany the Marxist chief-comrade [Obergenosse] Braun must force himself to act as if even he supported a revision.

One measures the greatness of Hitler’s personality and his successes hitherto by comparing him with the political figures of the new Germany, with the inept party-leaders in ministers’ chairs that were washed with the flood of ballots, with erstwhile imperial civil servants and officers that, operating mindlessly within a schematic conception of their duties, allowed themselves to be abused by Marxist governments contrary to the interests of the German people, and have even acquiesced in the disgraceful and intolerable slavery of the Young Plan.

Because of his successes and the growing strength of his movement, Hitler today is, even in the eyes of his opponents, a statesman who already influences, and in the not-distant future will decisively change, the development of the internal and external situation of the German people. For the millions of his supporters however he is already today more than a statesman: he is to them the leader that they follow enthusiastically in the struggle for the freedom and future of the German people. They have the conviction that the National-Socialist movement will absorb or destroy all other parties, and will finally unify in itself the entire German people. They have the conviction that Hitler will construct a new German Reich that will be internally more stable and outwardly stronger and more secure, and will last longer than the Reich of Bismarck. Hitler will give to the German people a new political worldview: through him and his movement the Germanic leadership will vanquish Judeo-Western parliamentarism; Nordic idealism will overcome Jewish Mammonism.

________________________________

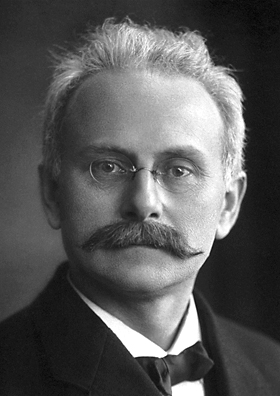

Johannes Stark (1874-1957) was a physicist who discovered in 1913 what came to be known as the Stark effect (the splitting of spectral lines in electric fields). This was foundational to the development of quantum theory. For the Stark effect and for the discovery of the Doppler effect in canal rays, Stark was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1919.

Johannes Stark (1874-1957) was a physicist who discovered in 1913 what came to be known as the Stark effect (the splitting of spectral lines in electric fields). This was foundational to the development of quantum theory. For the Stark effect and for the discovery of the Doppler effect in canal rays, Stark was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1919.