by Dr. Johannes Stark

I. From Hitler’s Life

The purpose of this work is the elucidation of the political aspects of Hitler’s personality in relation to his goals and achievements. Readers of the first edition have expressed the wish to read even more about his personality, especially about his life before rising to political prominence.

Adolf Hitler was born on 20 April 1889 in the small Bavarian-Austrian border-town of Braunau; he is thus in his 42nd year of life. His forebears were farmers of the Baiuwarian tribe. His father was a mid-level Austrian customs official.

Hitler grew up in the country; he was brought up Catholic and attended the first years of Realschule (secondary school) in the upper-Austrian city of Linz. At the age of 13 he lost his father; at 16, his mother. He did not want to become a government official but a painter, and later, at the suggestion of teachers at the art-academy, an architect. For this purpose he went at the age of 16 to Vienna. The nature of his activity in the following five years of his life meanwhile was dictated to him by his utter destitution following the death of his mother. About his life in Vienna he himself reports in his book Mein Kampf with the following words:

Five years of suffering and woe are embodied for me in the name of this Phaeacian city. Five years, in which I had to earn my bread first as an unskilled laborer, then as a smalltime painter; my truly meager bread, which of course never was enough to pacify even normal hunger. Hunger at that time was my loyal guardian, the only one who almost never abandoned me, who candidly shared with me in everything. Every book that I acquired stimulated his participation; a visit to the opera would have him keeping me company for days on end; it was a permanent struggle with my compassionless friend. And yet in this period I learned as never before. Apart from my architecture, apart from rare visits to the opera in lieu of eating, I had as my only friends just more books.

Back then I read infinitely much, and yet thoroughly. Whatever remained to me of free time from my work was given entirely to study. In a few years in this manner I created for myself the foundations of my knowledge, from which I benefit even today.

In any case this period before the war was the happiest and by far most satisfying of my life. If my income was still quite meager, I certainly did not live to be able to paint, but painted in order thereby to secure for myself the potential of my life, in other words, to make possible my further study. — What interested me the most, apart from my professional work, was also again here the study of daily political events, especially actions in foreign policy.

Upon a hill southward from Wervick we had come into hours of drumfire of gas-grenades that continued through the whole night in a more or less constant manner. Already toward midnight some comrades had passed out, some of them never to awaken. Toward morning the pain gripped me too, worse from one quarter-hour to the next, and around seven o’clock in the morning I stumbled and staggered toward the rear, carrying my last dispatch of the war.

Already some hours later my eyes had transformed into glowing coals; around me was darkness.

Thus I came into the Pasewalk military hospital in Pomerania, and there I had to live through the greatest disgrace of the century.

Since the day when I stood at the grave of my mother, I had not wept. Whenever in my youth Destiny laid hold of me with pitiless harshness, my defiance grew. When, in the long years of war, death took from our ranks so many a dear comrade and friend, it would have seemed to me almost a sin to cry: they died after all for Germany! And finally even in the last days of the terrible struggle, as the slithering gas fell upon me and began to eat into my eyes, and I, amid the fear of being forever blind, was momentarily inclined to give up hope, then the voice of conscience thundered to me: You miserable complainer, perhaps you want to wail while thousands have it hundreds of times worse than you, and so I endured my lot lethargic and silent. Now however I could no longer refrain. Now I saw for the first time how little all personal suffering mattered compared to the misfortune of the Fatherland.

[…]The more I tried to gain a clear understanding in this hour of the monstrous event, the more the shame of indignation and dishonor burned into my brow. What was all the pain of my eyes compared to this lament?

What followed were excruciating days and even worse nights. — I knew that all was lost. To place hope in the mercy of the enemy is at best the behavior of fools — or liars and criminals.

I resolved however to become a politician.

And Adolf Hitler has transformed his resolve to become a politician into reality in a manner and with a success of which German history knows no other example. The present work should demonstrate this.

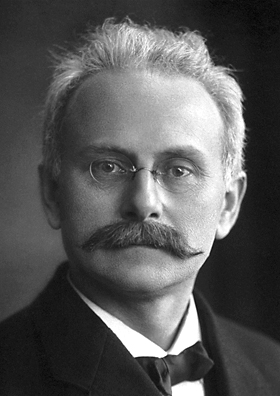

Johannes Stark (1874-1957) was a physicist who discovered in 1913 what came to be known as the Stark effect (the splitting of spectral lines in electric fields). This was foundational to the development of quantum theory. For the Stark effect and for the discovery of the Doppler effect in canal rays, Stark was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1919.

Johannes Stark (1874-1957) was a physicist who discovered in 1913 what came to be known as the Stark effect (the splitting of spectral lines in electric fields). This was foundational to the development of quantum theory. For the Stark effect and for the discovery of the Doppler effect in canal rays, Stark was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1919.